QUICK VIEW:

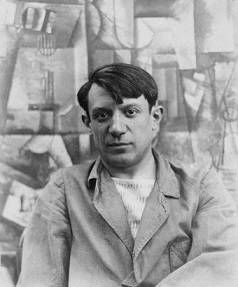

Pablo

Picasso was the most dominant and influential artist of the first half

of the twentieth century. Associated most of all with pioneering Cubism, alongside Georges Braque, he also invented collage, and made major contributions to Symbolism, Surrealism,

and to the classical styles of the 1920s. He saw himself above all as

a painter, and yet his sculpture was greatly influential, and he also

explored areas as diverse as print-making and ceramics. Finally, he

was a famously charismatic personality: his many relationships with

women not only filtered into his art but may have directed its course;

and his behavior has come to embody that of the bohemian modern artist

in the popular imagination.

Key Ideas

- Picasso first emerged as a Symbolist influenced by the likes of Munch and Toulouse-Lautrec,

and this tendency shaped his so-called Blue Period, in which he

depicted beggars and prostitutes and various urban misfits, and also

the brighter moods of his subsequent Rose Period. - It was a confluence of influences - from Paul Cézanne and Henri Rousseau,

to archaic and tribal art - that encouraged Picasso to lend his

figures more weight and structure around 1906. And they ultimately set

him on the path towards Cubism,

in which he deconstructed the conventions of perspectival space that

had dominated painting since the Renaissance. These innovations would

have far-reaching consequences for practically all of modern art,

revolutionizing attitudes to the depiction of form in space. - Picasso's immersion in Cubism also eventually led him to the

invention of collage, in which he abandoned the idea of the picture as a

window on objects in the world, and began to conceive it merely as an

arrangement of signs which used different, sometimes metaphorical

means, to refer to those objects. This too would prove hugely

influential for decades to come. - Picasso had an eclectic attitude to style, and although, at any one

time, his work was usually characterized by a single dominant

approach, he often moved interchangeably between different styles -

sometimes even in the same artwork. - His encounter with Surrealism

in mid 1920s, although never transforming his work entirely,

encouraged a new expressionism which had been suppressed throughout

the years of experiment in Cubism and subsequently during the early

1920s when his style was predominantly classical. This development

enabled not only the soft forms and tender eroticism of his portraits

of his mistress Marie-Therese Walter, but also the starkly angular

imagery of Guernica, the century's most famous anti-war painting. - Picasso was always eager to place himself in history, and some of his greatest works, such as Les Demoiselles d'Avignon,

refer to a wealth of past precedents - even while overturning them.

As he matured he became only more conscious of assuring his legacy, and

his late work is characterized by a frank dialogue with Old Masters

such as Ingres, Velazquez, Goya, and Rembrandt.

DETAILED VIEW:

Childhood

Pablo

Ruiz Picasso was born into a creative family. His father was a

painter, and he quickly showed signs of following the same path: his

mother claimed that his first word was "piz," a shortened version of lapiz,

or pencil; and his father would be his first teacher. Picasso began

formally studying art at the age of eleven. Several paintings from his

teenage years still exist, such as First Communion (1895), which

is typical in its conventional, if accomplished, academic style. His

father groomed the young prodigy to be a great artist by getting

Picasso the best education the family could afford, visiting Madrid to

see works by Spanish old masters. And when the family moved to

Barcelona, so his father could take up a new post, Picasso continued

his art education.

Ruiz Picasso was born into a creative family. His father was a

painter, and he quickly showed signs of following the same path: his

mother claimed that his first word was "piz," a shortened version of lapiz,

or pencil; and his father would be his first teacher. Picasso began

formally studying art at the age of eleven. Several paintings from his

teenage years still exist, such as First Communion (1895), which

is typical in its conventional, if accomplished, academic style. His

father groomed the young prodigy to be a great artist by getting

Picasso the best education the family could afford, visiting Madrid to

see works by Spanish old masters. And when the family moved to

Barcelona, so his father could take up a new post, Picasso continued

his art education.

Early Training

It

was in Barcelona that Picasso first matured as a painter. He

frequented the Els Quatre Gats, a cafe popular with bohemians,

anarchists, and modernists. And he came to be familiar with Art Nouveau and Symbolism, and artists such as Edvard Munch and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec.

It was here that he met Jaime Sabartes, who would go on to be his

fiercely loyal secretary in later years. This was his introduction to a

cultural avant-garde, in which young artists were encouraged to

express themselves.

During the years from 1900 to 1904 Picasso travelled frequently,

spending time in Madrid and Paris, in addition to spells in Barcelona.

Although he began making sculpture during this time, critics

characterize this time as his Blue Period, after the blue/grey palette

that dominated his paintings. The mood of the work was also insistently

melancholic. One might see the beginnings of this in the artist's

sadness over the suicide of Carlos Casegemas, a friend he has met in

Barcelona, though the subjects of much of the Blue Period work were

drawn from the beggars and prostitutes he encountered in city streets.

The Old Guitarist (1903) is a typical example of both the subject

matter and the style of this phase.

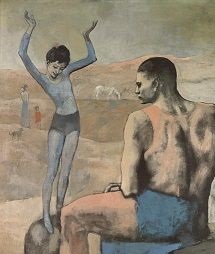

In 1904 Picasso's palette began to brighten, and for a year or more he

painted in a style that has been characterized as his Rose Period. He

focussed on performers and circus figures, switching his palette to

various shades of more uplifting reds and pinks. And around 1906, soon

after he had met Georges Braque, his palette darkened, his forms became heavier and more solid in aspect, and he began to find his way towards Cubism.

was in Barcelona that Picasso first matured as a painter. He

frequented the Els Quatre Gats, a cafe popular with bohemians,

anarchists, and modernists. And he came to be familiar with Art Nouveau and Symbolism, and artists such as Edvard Munch and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec.

It was here that he met Jaime Sabartes, who would go on to be his

fiercely loyal secretary in later years. This was his introduction to a

cultural avant-garde, in which young artists were encouraged to

express themselves.

During the years from 1900 to 1904 Picasso travelled frequently,

spending time in Madrid and Paris, in addition to spells in Barcelona.

Although he began making sculpture during this time, critics

characterize this time as his Blue Period, after the blue/grey palette

that dominated his paintings. The mood of the work was also insistently

melancholic. One might see the beginnings of this in the artist's

sadness over the suicide of Carlos Casegemas, a friend he has met in

Barcelona, though the subjects of much of the Blue Period work were

drawn from the beggars and prostitutes he encountered in city streets.

The Old Guitarist (1903) is a typical example of both the subject

matter and the style of this phase.

In 1904 Picasso's palette began to brighten, and for a year or more he

painted in a style that has been characterized as his Rose Period. He

focussed on performers and circus figures, switching his palette to

various shades of more uplifting reds and pinks. And around 1906, soon

after he had met Georges Braque, his palette darkened, his forms became heavier and more solid in aspect, and he began to find his way towards Cubism.

Mature Period

In

the past critics dated the beginnings of Cubism to his early

masterpiece Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907). Although that work is now

seen as transitional (lacking the radical distortions of his later

experiments), it was clearly crucial in his development since it was

heavily influenced by African sculpture and ancient Iberian art. It is

said to have inspired Braque to paint his own first series of Cubist

paintings, and in subsequent years the two would mount one of the most

remarkable collaborations in modern painting, sometimes eagerly

learning from each other, at other times trying to outdo one another in

their fast-paced and competitive race to innovate. They visited each

other daily during their formulation of this radical technique, and

Picasso described himself and Braque as "two mountaineers, roped

together." In their shared vision, multiple perspectives on an object

are depicted simultaneously by being fragmented and rearranged in

splintered configurations. Form and space became the most crucial

elements, and so both artists restricted their palettes to earth tones,

in stark contrast with the bright colors used by the Fauves that had preceded them.

Picasso rejected the label "Cubism," especially when critics began to

differentiate between the two key approaches he pursued - Analytic and

Synthetic. He saw his body of work as a continuum. But it is beyond

doubt that there was a change in his work around 1912. He became less

concerned with representing the placement of objects in space than in

using shapes and motifs as signs to playfully allude to their presence.

He developed the technique of collage, and from Braque he learned the

related method of papiers colles, which used cut-out pieces of

paper in addition to fragments of existing materials. This phase has

since come to be known as the "Synthetic" phase of Cubism, due to its

reliance on various allusions to an object in order to create the

description of it. This approach opened up the possibilities of more

decorative and playful compositions, and its versatility encouraged

Picasso to continue to utilise it well in the 1920s.

But the artist's dawning interest in ballet also sent his work in new

directions around 1916. This was in part prompted by meeting the poet,

artists and filmmaker Jean Cocteau. Through him he met Serge Diaghilev, and went on to produce numerous set designs for the Ballets Russes.

For some years Picasso had occasionally toyed with classical imagery,

and he began to give this free rein in the early 1920s. His figures

became heavier and more massive, and he often imaging them against

backgrounds of a Mediterranean Golden Age. They have long been

associated with the wider conservative trends of culture's so-called rappel a l'ordre ("return to order") in the 1920s.

His encounter with Surrealism

in the mid 1920s again prompted a change of direction. His work became

more expressive, and often violent or erotic. This phase in his work

can also be correlated with the period in his personal life when his

marriage to dancer Olga Koklova began to break down and he began a new

relationship with Marie-Therese Walter. Indeed, critics have often

noted how changes in style in Picasso's work often go hand in hand with

changes in his romantic relationships: his partnership with Koklova

spanned the years of his interest in dance and, later, his time with

Jacqueline Roque is associated with his late phase in which he became

preoccupied with his legacy alongside the old masters. Picasso

frequently painted the women he was in love with, and as a result his

tumultuous personal life is well represented on canvas. He was known to

have kept many mistresses, most famously Eva Gouel, Dora Maar and

Francoise Gilot. He married twice, and had four children, Claude,

Paloma, Maia, and Paolo.

In the late 1920s he began a collaboration with the sculptor Julio Gonzalez.

This was his most significant creative partnership since he had worked

alongside Braque, and it culminated in some welded metal sculptures

which were subsequently highly influential.

As the 1930s wore on, political concerns began to cloud Picasso's view,

and these would continue to preoccupy him for some time. His disgust at

the bombing of civilians in the Basque town of Guernica, during the

Spanish Civil War, prompted to create the painting Guernica, in

1937. During WWII he stayed in Paris, and the German authorities left

him sufficiently unmolested to allow him to continue work. However, the

war did have a huge impact on Picasso, with his Paris painting

collection confiscated by Nazis and some of his closest Jewish friends

killed. Picasso made works commemorating them - sculptures employing

hard, cold materials such as metal, and a particularly violent follow

up to Guernica, entitled The Charnel House (1945).

Following the war he was also closely involved with the Communist

Party, and several major pictures from this period, such as War in Korea (1951), make that new allegiance clear.

the past critics dated the beginnings of Cubism to his early

masterpiece Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907). Although that work is now

seen as transitional (lacking the radical distortions of his later

experiments), it was clearly crucial in his development since it was

heavily influenced by African sculpture and ancient Iberian art. It is

said to have inspired Braque to paint his own first series of Cubist

paintings, and in subsequent years the two would mount one of the most

remarkable collaborations in modern painting, sometimes eagerly

learning from each other, at other times trying to outdo one another in

their fast-paced and competitive race to innovate. They visited each

other daily during their formulation of this radical technique, and

Picasso described himself and Braque as "two mountaineers, roped

together." In their shared vision, multiple perspectives on an object

are depicted simultaneously by being fragmented and rearranged in

splintered configurations. Form and space became the most crucial

elements, and so both artists restricted their palettes to earth tones,

in stark contrast with the bright colors used by the Fauves that had preceded them.

Picasso rejected the label "Cubism," especially when critics began to

differentiate between the two key approaches he pursued - Analytic and

Synthetic. He saw his body of work as a continuum. But it is beyond

doubt that there was a change in his work around 1912. He became less

concerned with representing the placement of objects in space than in

using shapes and motifs as signs to playfully allude to their presence.

He developed the technique of collage, and from Braque he learned the

related method of papiers colles, which used cut-out pieces of

paper in addition to fragments of existing materials. This phase has

since come to be known as the "Synthetic" phase of Cubism, due to its

reliance on various allusions to an object in order to create the

description of it. This approach opened up the possibilities of more

decorative and playful compositions, and its versatility encouraged

Picasso to continue to utilise it well in the 1920s.

But the artist's dawning interest in ballet also sent his work in new

directions around 1916. This was in part prompted by meeting the poet,

artists and filmmaker Jean Cocteau. Through him he met Serge Diaghilev, and went on to produce numerous set designs for the Ballets Russes.

For some years Picasso had occasionally toyed with classical imagery,

and he began to give this free rein in the early 1920s. His figures

became heavier and more massive, and he often imaging them against

backgrounds of a Mediterranean Golden Age. They have long been

associated with the wider conservative trends of culture's so-called rappel a l'ordre ("return to order") in the 1920s.

His encounter with Surrealism

in the mid 1920s again prompted a change of direction. His work became

more expressive, and often violent or erotic. This phase in his work

can also be correlated with the period in his personal life when his

marriage to dancer Olga Koklova began to break down and he began a new

relationship with Marie-Therese Walter. Indeed, critics have often

noted how changes in style in Picasso's work often go hand in hand with

changes in his romantic relationships: his partnership with Koklova

spanned the years of his interest in dance and, later, his time with

Jacqueline Roque is associated with his late phase in which he became

preoccupied with his legacy alongside the old masters. Picasso

frequently painted the women he was in love with, and as a result his

tumultuous personal life is well represented on canvas. He was known to

have kept many mistresses, most famously Eva Gouel, Dora Maar and

Francoise Gilot. He married twice, and had four children, Claude,

Paloma, Maia, and Paolo.

In the late 1920s he began a collaboration with the sculptor Julio Gonzalez.

This was his most significant creative partnership since he had worked

alongside Braque, and it culminated in some welded metal sculptures

which were subsequently highly influential.

As the 1930s wore on, political concerns began to cloud Picasso's view,

and these would continue to preoccupy him for some time. His disgust at

the bombing of civilians in the Basque town of Guernica, during the

Spanish Civil War, prompted to create the painting Guernica, in

1937. During WWII he stayed in Paris, and the German authorities left

him sufficiently unmolested to allow him to continue work. However, the

war did have a huge impact on Picasso, with his Paris painting

collection confiscated by Nazis and some of his closest Jewish friends

killed. Picasso made works commemorating them - sculptures employing

hard, cold materials such as metal, and a particularly violent follow

up to Guernica, entitled The Charnel House (1945).

Following the war he was also closely involved with the Communist

Party, and several major pictures from this period, such as War in Korea (1951), make that new allegiance clear.

Late Years and Death

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Picasso worked on his own versions of canonical masterpieces by artists such as Nicolas Poussin, Lucas Cranach, Diego Velazquez, and El Greco.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Picasso worked on his own versions of canonical masterpieces by artists such as Nicolas Poussin, Lucas Cranach, Diego Velazquez, and El Greco.In the latter years of his life, Picasso sought solace from his

celebrity, marrying Jacqueline Rogue in 1961. His later paintings were

heavily portrait-based and their palettes nearly garish in hue. Critics

have generally considered them inferior to his earlier work, though in

recent years they have been more enthusiastically received. He also

created many ceramic and bronze sculptures during this later period.

He died in the South of France in 1973.

Legacy

Picasso's

influence was profound and far-reaching for most of his life. His work

in pioneering Cubism established a set of pictorial problems, devices

and approaches, which remained important well into the 1950s. And at

each stage of his career, from the classical works of the 1920s to the

works produced in occupied Paris during the 1940s, his example was

important. Even after the war, even though the energy in avant-garde art

shifted to New York, Picasso remained a titanic figure, and one who

could never be ignored. Indeed, even though the Abstract Expressionists

could be said to have superseded aspects of Cubism (even while being

strongly influenced by him), The Museum of Modern Art in New York has

been called "the house that Pablo built," because it has so widely

exhibited the artist's work. MoMA's opening exhibition in 1930 included

fifteen paintings by Picasso. He was also a part of Alfred Barr's highly influential survey shows, Cubism and Abstract Art and Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism.

Although his influence undoubtedly waned in the 1960s, he had by that

time become a Pop icon, and the public's fascination with his life

story continue to fuel interest in his work.

influence was profound and far-reaching for most of his life. His work

in pioneering Cubism established a set of pictorial problems, devices

and approaches, which remained important well into the 1950s. And at

each stage of his career, from the classical works of the 1920s to the

works produced in occupied Paris during the 1940s, his example was

important. Even after the war, even though the energy in avant-garde art

shifted to New York, Picasso remained a titanic figure, and one who

could never be ignored. Indeed, even though the Abstract Expressionists

could be said to have superseded aspects of Cubism (even while being

strongly influenced by him), The Museum of Modern Art in New York has

been called "the house that Pablo built," because it has so widely

exhibited the artist's work. MoMA's opening exhibition in 1930 included

fifteen paintings by Picasso. He was also a part of Alfred Barr's highly influential survey shows, Cubism and Abstract Art and Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism.

Although his influence undoubtedly waned in the 1960s, he had by that

time become a Pop icon, and the public's fascination with his life

story continue to fuel interest in his work.

ARTISTIC INFLUENCES:

Below are Pablo Picasso's major influences, and the people and ideas that he influenced in turn.

ARTISTS

Francisco Goya

El Greco

Paul Gauguin

Paul Cézanne

Henri Matisse

CRITICS/FRIENDS

Guillaume Apollinaire

Gertrude Stein

Georges Braque

Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler

Ambroise Vollard

MOVEMENTS

Impressionism

Post-Impressionism

Expressionism

Art Nouveau

African Art

Years Worked: 1892 - 1973

CRITICS/FRIENDS

Alfred H. Barr, Jr.

Clement Greenberg

Meyer Schapiro

Robert Rosenblum

MOVEMENTS

Cubism

Abstract Art

Surrealism

Pop Art

Quotes

"Every act of creation is first an act of destruction."

"Our goals can only be reached through a vehicle of a plan, in which we

must fervently believe, and upon which we must vigorously act. There is

no other route to success."

"For those who know how to read, I have painted my autobiography"

"Our goals can only be reached through a vehicle of a plan, in which we

must fervently believe, and upon which we must vigorously act. There is

no other route to success."

"For those who know how to read, I have painted my autobiography"

Pablo Picasso

4/

5

Oleh

Unknown

Tinggalkan Jejak Anda Dengan Berkomentar